Digitizing the Andes

** This post draws from a talk I gave at the Congreso Internacional de Peruanistas en el Extranjero at Georgetown University on October 13, 2013.

Technology in the Academy

Academia’s relationship to technology remains complicated, ambivalent, and constantly changing. There would be few among us who would disagree that the internet, email, and digital technology have exerted a tremendous impact on the way that we conduct research. Networked journals enable us to download thousands of scholarly articles in PDF format at lightning speeds, which for the technologically savvy among us, can subsequently be loaded onto iPads and e-readers for a completely paperless reading experience. Email, Facebook, and Twitter enable us to freely communicate with colleagues across the globe. Archival research in repositories abroad that would have originally cost thousands of dollars and months of research travel can now be conducted from the comforts of home thanks to digitization projects carried out by libraries worldwide. Yet technology does not come without its consequences. Professors bemoan the seeming inability of undergraduates to focus on one thing at a time. Entire research papers can be completed without a student ever having to enter into the physical space of the library. And I’m sure there are many among us, though we may be reluctant to admit it, who have been tempted to fact-check using google rather than dragging ourselves into the musty stacks to make sure we’re 1000% correct on the date of that one obscure event definitively referenced in a work that hasn’t been digitized on google books. We could spend days debating the benefits and consequences of technology in the realm of academic inquiry. But what I would like to do here is to lay out in broad strokes the impact of digital media in my particular area of specialty—pre-Columbian and colonial Andean art.

Digitizing Mesoamerica

To begin, I’d actually like to introduce an early project that has nothing to do with the Andes, but will serve as an important point of departure for thinking about the development of digital projects related to this field over the past decade. Produced in conjunction with the Mint Museum of Art’s blockbuster 2002 exhibition, “The Sport of Life and Death: The Mesoamerican Ballgame,” this website offers an interactive overview of the pre-Columbian Mesoamerican ballgame, complete with images of some of the objects included in the exhibition as well as videos of modern-day people playing the game in Mexico and Central America. This site participated in the early stages of an incipient “infotainment” or “digital pedagogy” pioneered by art and natural history museums long before the “digital humanities” had become a household name. It was clearly ahead of its time, winning a slew of awards for its sleek interface and high educational value. It wouldn’t be for another decade that these kinds of projects would become almost a pre-requisite for any successful international exhibition of its caliber. This website, along with other kinds of digital projects, served as an important starting point for a rich trajectory of Digital Humanities projects devoted to the dissemination of scholarship on pre-Columbian and colonial Mesoamerican visual cultures, whether we’re talking about the World Digital Library’s full digitization of the Florentine Codex (which Renee wrote about here), or this recent article by Barbara Mundy for the experimental online journal, Appendix, which offers us an interactive experience with a colonial Mexican map. What makes this particular project unique is that it utterly transforms the traditional format of art historical texts by moving us through cartographic space via digital and textual interventions. We are not simply witnessing a digitization of a document or image, but the development of a dynamic open-source format that facilitates new ways of seeing and reading.

Digitizing the Andes

The development of Digital Humanities projects related to Andean visual culture have not occurred with the same frequency and scope as their Mesoamerican and Caribbean counterparts. The reasons for this are manifold, ranging from differential institutional resources and funding to support such projects, to the current structure of tenure evaluation that discourages many junior scholars from pursuing scholarly work outside of a peer review, print culture framework. Nevertheless, the resources that we do have a rich and diverse. Perhaps the most well-known and heavily utilized digitization project in the realm of Andean Studies is the Royal Library of Copenhagen’s digitization and transcription of Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala’s El primer nueva corónica i buen gobierno. Guaman Poma was a native Andean chronicler from the modern-day Ayacucho region of Peru. His nearly 1200-page manuscript replete with 398 hand-drawn illustrations provided a monumental platform to persuade King Philip III of the failures of the Spanish colonial administration and the ability for native Andeans to govern themselves. A number of articles available online that detail Guaman Poma’s manuscript can be found here. This fantastic resource enables visitors to view the manuscript page by page and download medium and high-resolution images of Guaman Poma’s illustrations. Here, we have a strong correspondence between the visibility of the site and the visibility of Guaman Poma’s work within Andean scholarship. That is to say, almost anyone whose research even tangentially touches on Guaman Poma knows about this site. Indeed, the site’s high international traffic makes it the first link to appear in a web search, even before Wikipedia’s entry on Guaman Poma. With the impending Wikipediafication of the internet in full swing, this is no easy feat.

Another site of tremendous importance to Andean visual culture is PESSCA (Project on Engraved Sources of Spanish Colonial Art). Spearheaded by Almerindo Ojeda of UC Davis and various Peruvian institutions including the Universidad Católica and the Colección Barbosa-Stern. This website utilizes the practice of crowdsourcing to compile the largest database of “correspondences” between colonial Latin American paintings and European prints. Founded in 2005, the site currently has over 2,000 correspondences and the number increases daily. While it originated as a Peruvian resource, the site now includes substantial paintings from Mexico, Ecuador, and Bolivia matched up to their European print sources.

To take just one example, the site provides us with Roman engraver Philippe Thomassin’s Last Judgment from 1606 and the various paintings it inspired in the American viceroyalties:

Philippe Thomassin, The Last Judgment, 1606. Source: http://colonialart.org/archive/artList?row=251&col=939a-946b

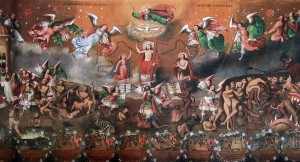

José López de Ríos, Last Judgment, Church of Carabuco, La Paz, Bolivia, 1684. Source: http://colonialart.org/archive/artList?row=251&col=939a-946b

Tadeo Escalante, Last Judgment, Church of Huaro, Quispicanchis, Cuzco, Peru, 1802. Photo by Ananda Cohen Suarez

In fact, the site enables users to subscribe to its RSS feed so that they can keep up with all of the new content being added to the site. This resource is absolutely essential for anyone working in colonial Andean art. Yet unlike the Guaman Poma site, this resource is far less visible; few reference it in their publications and it does not always show up in web searches. There is a low correspondence between the utility of the resource and its scholarly reach.

There are a number of museum websites that contain high resolution images of pre-Columbian and colonial Andean artworks. The Metropolitan Museum of Art contains not only high quality photographs of Paracas, Nazca, Moche, Sicán, Wari, and Inca objects on display, but it has also digitized its entire collection of colonial Andean textiles. The Brooklyn Museum of Art, famously known for a number of iconic colonial Andean paintings such as the portrait of Doña María Belsunse y Salasar, a 1763 painting of Our Lady of Cocharcas, and portraits of Inca rulers, has an edgier, more contemporary interface that allows users to search for “tags” or keywords, and to create image groups. Some of the artworks even show x-ray images taken by the conservation lab [image]. This past summer, LACMA recently placed thousands of images from its collections in the public domain, a true game changer for Latin American art historians wishing to utilize them for web or print publication. It should be noted that the digitization of collections is not limited to US museums; the Museo de Arte de Lima recently partnered with Google Art Project to make high-resolution images of its collection available online.

With digitization projects in full swing, we can expect to continue to gain access to a number of works of art that are otherwise unavailable for viewership, whether in private collections or museums that require long-distance travel. The production of high-quality photographs of images inevitably enriches our own research and pedagogical capacities as educators. For instance, when I teach colonial Latin American art history, I can access the full zodiac series by the 17th-century native Andean artist Diego Quispe Tito in color, each paired with its European source image.

This undoubtedly enables me to teach more effectively and expose students to the entire series rather than 1-2 images from it that are widely reproduced in books. But on the other hand, what is still lacking in these digital humanities projects is the next step—that is, now that we have digitized astounding numbers of images, what do we do with them? How can we utilize digital media to produce dynamic scholarship and pedagogical tools? How might digital technology help bring images to life and engage with their viewers in meaningful ways beyond the tired formula of text + image? A central goal of my own scholarship on mural painting of the colonial Andes is to argue that murals require a bodily engagement with their viewers given their immense size and embeddedness in architecture.

17th-century murals at the Chapel of Canincunca, Quispicanchis, Cuzco, Peru. Photo by Ananda Cohen Suarez

When they are merely reproduced on a page, isolated and cropped, the format of the publication merely reinscribes the framework that I am trying to escape. I highlight my own work as a means of thinking through these issues, but ultimately what I would like to underscore is the need for us to take the next step—after digitization happens, we need to conceive of creative ways to utilize these images that will impact the scholarly community and general public. Otherwise, we risk recreating the very boundaries that a democratized media format seeks to dismantle. Traditional scholarship often produced divisions and obstacles across national borders, whereby US, European, and Latin American scholars were not always in dialogue with one another. While digital scholarship has amended some of those divisions it also holds the potential to create new fractures—that is, generational divides, divisions between the tech-savvy and the not-so-savvy. As digital modes of seeing, learning, and sharing continue to unfold, we must be cognizant of the specific ways we wish to utilize it as a form of public dialogue and scholarly engagement that remains inclusive, user-friendly, and encourages new voices and perspectives.